Click for bigger version

This essay was originally published in The Book Review India.

If you’ve read Delirious Delhi, then this essay is essentially an epilogue: a postscript about the expat’s post-India life, and what it’s like to have lived in India and miss it so very much.

Delhi: The Lament of the Hungry Ex-Expat

By Dave Prager

I spotted the Indians entering Denver’s Botanic Gardens about fifty feet ahead of us. It was their clothes that got me excited: both ladies in the family wore saris.

I nudged Jenny with excitiment. She sighed. “Dave, this is getting creepy.”

Creepy? Since when is it creepy to follow strange Indians around a park hoping to catch their eyes, start a conversation, win their trust, become friends, exchange numbers, and accept an invitation to dinner—all because I want to eat homemade Indian food again?

I mean, doesn’t every American who once lived in Delhi do that?

* * *

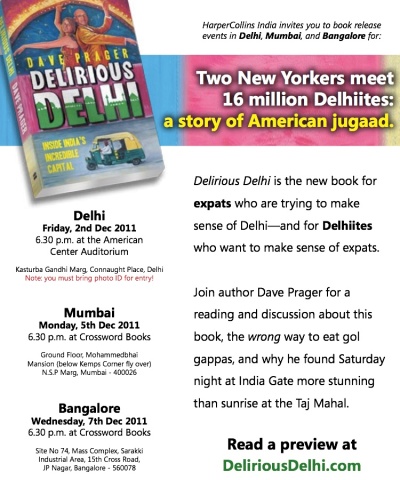

The year-and-a-half my wife Jenny and I lived in Delhi’s Hauz Khas Market neighborhood changed me forever. Not just because of the career boost from my promotion to the Gurgaon office. And not just because the book I wrote about Delhi is spinning through HarperCollins India’s printing facilities even as this essay goes to print. No, it’s mostly because now that I’m gone, my stomach forces my brain to view every Indian I see as a potential conduit to the food I miss so much.

I’m not trying to be creepy. I just miss the food.

Before we moved to Delhi, I had no appreciation for the dynamics of the cuisine. I was perfectly content with the cheapest Indian buffet serving the stalest garlic naan and the driest tandoori chicken. In those innocent times, every dish on every menu sounded equally exotic and exciting; I’d order whatever I didn’t recognize and, with full ignorance as to both the quality and the composition of what I was eating, enjoy every bite of it.

But in the years since we’ve left Delhi, not a single Indian restaurant has achieved even the standards of my office canteen’s watery dal. I’ve yet to taste a paneer as milky and smooth as that from Saket Select Citywalk Mall food court. And even Singapore’s top-rated Indian restaurants were just a distant echo of what was, to me, the gold standard of Indian food: the meals our maid Ganga would cook for us three times a week.

(Wikipedia tells us that Annupurna is the Hindu goddess of food; experience tells us that Ganga is her earthly manifestation.)

We’ve tried the trendiest Indian restaurant on Denver’s South Pearl Street, the Singapore branch of Saravana Bhavan, and a dhaba in the back of a suburban Indian grocery in Aurora, Colorado; I’ve departed them all with my belly full but my heart empty. I’ve even purchased the same MDH spice boxes that Ganga used to cook her heavenly meals for us, faithfully following the recipes printed on the back and failing each time to come anywhere close.

Which is why I stare so hungrily at every Indian that I see.

* * *

We’re in a restaurant in Estes Park, Colorado, a mountain town near one of America’s most spectacular national parks. A bagel is in my hands but my tongue is tasting creamy dal makhani, because all I can focus on are the unmistakable accents emanating from the couple at the table next to us. They’re discussing hiking routes and camping spots; I’m hearing menu plans and cooking instructions.

“Where are you from?” I ask, leaning towards their table, hoping the answer is “Nizamuddin East” so that our conversation flows easily to kebab stands and butter chicken.

The man looks up. “Seattle,” he tells me, curtly. He turns back to his map.

I return to my bagel. Now it just tastes like a bagel.

* * *

After leaving Delhi, Jenny and I spent a year in Singapore and then returned to the States to start a family. Success: our baby daughter Georgiana is sweet, adorable, and the perfect tool to aid my quest to ingratiate myself to Indians.

She first played her part at the San Francisco airport. Approaching the gate for our flight back to Denver, I spotted an Indian couple and their infant son. Bells clanged in my head: she was wearing a salwar. Which meant she was born and bred outside the US.

I innocuously steered George’s stroller toward them.

Jenny rolled her eyes and walked off to get coffee.

I sat a few seats down from them, removed George from her stroller, and engaged in a deliberately-conspicuous bout of tongue-waggling and noise-making. Sure enough, George’s irresistible smile drew their eyes; and that was the opening I needed.

“How old is your son?” I asked. I didn’t actually care how old he was; I just wanted to confirm their accents. And as they proudly boasted that Nikhil or Naveen or something was a year or eighteen months or seven or whatever, all that my brain registered were pronunciations that implied a childhood immersed in sambar. With chicken biryani clouding my thoughts and phantom thalis teasing my nostrils, I exclaimed (loudly, to mask my stomach’s rumbling): “Oh! You’re from India! We lived there for eighteen months!”

And from there, the conversation progressed just as I’d hoped. They were from Chennai, but they knew Delhi, and together we grew pleasantly melancholy reminiscing about places and tastes that were, for both of us, equally dear and equally far. By the time Jenny joined us with her coffee, we were chatting about old days like old friends, contrasting our transitions to each other’s cultures, recalling the restaurants we missed the most, and jointly lamenting the fact that nobody knows how to cook an uttapam west of Chowpatti Beach.

* * *

My nostalgia for Delhi generally fixates on food, but it can go deeper. At three o’clock on a workday, for instance, I’ll look blearily up from my computer and fantasize about the chaiwallah outside my Gurgaon office, just seven thousand miles to my left. Had it been three o’clock in that office, Dipankar and Murali and I would have paid him a visit and enjoyed his five-rupee respite from our responsibilities.

(Although this moment of freedom, too, leads my mind back to food. Because here in America, as I stand by the coffee maker, the nearest snack is at a convenience store a mile away. How can my country be considered a world leader when we’re so lacking in sidewalk samosa vendors?)

At these times, when I’m missing the camaraderie as much as the cuisine, I turn to the Internet. I vicariously join my Delhi friends as they motorcycle to Leh or eat parathas in Old Delhi. I toast the country on Republic Day. I cheer cricket players on a first-name basis. And I join them in experiencing the changing capital city—like when my former coworker Nobin switched from the office cab to the Delhi Metro for his commute to Gurgaon. From his seat, he Tweeted praise at the shining municipal infrastructure that warmed me in my chair half a world away.

I’ve even grown nostalgic for Delhi’s traffic, of all things. Imagine getting misty-eyed for MG Road! But it’s happened: though there was nothing in Delhi I hated more than my commute to Gurgaon, the traffic in Denver is, in a way, worse. Because when I descend the on-ramp into four orderly lanes of vehicles in which nobody honks, nobody jostles for advantage, and nobody takes to the shoulders to jump the queue, I realize that Delhi’s traffic, for all its misery, also contained a kind of freedom: the skill of the driver could alter the course of the jam. A good driver could seize ephemeral opportunities revealed by shifting vehicles to shave seconds off the commute, or to cross the Ring Road before the light turned red.

But Denver’s traffic is egalitarian in its oppression. Once you’re on the highway, you’re committed to the collective fate. Delhi’s traffic allows for individual heroics; Denver’s traffic is entirely communal.

* * *

But I live in America now. I accept it: derivative restaurants, watery tea, non-negotiable traffic, and streets that are empty of samosas.

Which is why I can’t imagine that I’m the only American creeping around Indians to spark culinary connections. Because those of us who left our stomachs in Safdarjung know that expat Indians must be coping with the same emptiness—except that expat Indians possess the wisdom to transform frozen okra and boxed spices into a glorious bhindi masala. They can tease bhangan bharta out of the most stoic eggplant. Their kitchens are their link to Delhi, and we former residents—or, at least, this former resident—want in.

So far, though, I’ve had no luck. At the San Francisco airport, for instance, our connection to that Indian couple was severed when boarding began for the Denver flight: only we stood up. Our new friends were waiting for a flight to Arizona, which meant that no dinner party was imminent.

Nor could I make any headway at that restaurant in Estes Park, where I looked up from my bagel with one last desperate attempt: “No, where are you originally from? India? Because we spent eighteen months living there!” To which the woman smiled gently and said, with finality, “Your daughter is beautiful.” Her tone left no further room for discussion.

Nor could I make it work at the Denver Botanic Gardens, where I’d spotted that Indian foursome entering ahead of us. Our meandering paths had crossed theirs a half-dozen times, despite Jenny’s best efforts to steer us away from them. Finally, near the Lilac Garden, I spotted my opening: the patriarch of the family was posing his wife, daughter, and son-in-law for a photo. I quickly offered to snap the four of them together.

He declined. In accented English. To which I replied in my own terrible Hindi, “Aap guessa hai!?”

The four of them looked at me.

“Hindi bollna?” I asked.

“Are you speaking Hindi?” the father finally asked me.

“Yes!” I beamed. “We lived in Delhi for a year-and-a-half.”

“Oh. We don’t speak much Hindi.”

They turned back to their photo. I turned back to my wife. And that night for dinner, I sautéed some onions and tomatoes, emptied a can of chick peas into the pan, and dumped in a few tablespoons of MDH channa masala mix.

It was not like Ganga’s at all.